Laser Cleaning Machine: Things You Must Know Before Buying, Using, or Building a Business Around It

Laser cleaning machines are often marketed as revolutionary tools—cleaner than sandblasting, safer than chemicals, faster than grinding, and more precise than all three. That reputation is not entirely wrong, but it is incomplete. Many buyers discover too late that laser cleaning is not a “plug-and-play miracle,” but a process technology that rewards preparation and punishes assumptions. The difference between success and disappointment rarely lies in laser physics; it lies in understanding what really matters before you buy, deploy, or commercialize a laser cleaning machine.

A laser cleaning machine can deliver exceptional technical and economic results—but only when the user understands its limits, process requirements, safety obligations, cost structure, and application fit. Treating it as a simple tool leads to underperformance; treating it as an engineered process unlocks its full value.

This guide is written for serious buyers, engineers, and business owners. It does not repeat marketing slogans. Instead, it covers the critical things you must know—from technology fundamentals and parameter logic to safety, cost, workflow integration, and long-term ownership realities. Because of the depth required, this guide is intentionally comprehensive and will be delivered in multiple parts to avoid shortcuts or superficial conclusions.

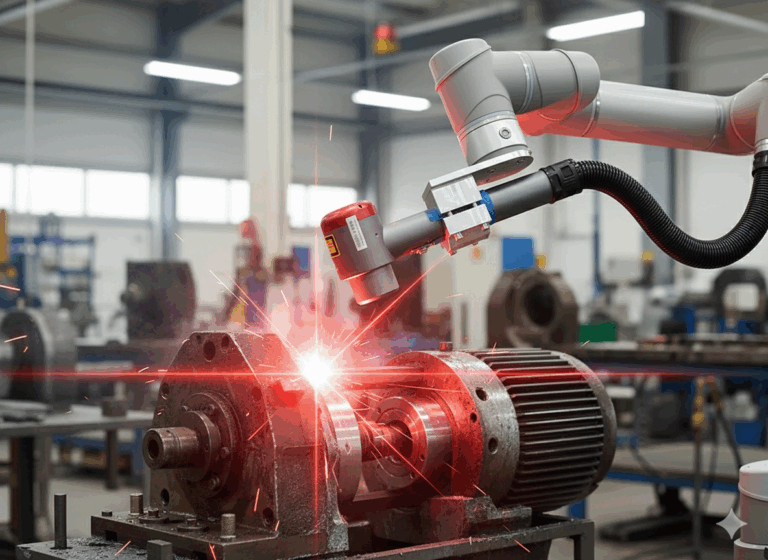

Understanding the Technology Beyond the Brochure

100W Fiber Laser Cleaning Machine

100W Fiber Laser Cleaning Machine

What a Laser Cleaning Machine Really Is (and Is Not)

At its core, a laser cleaning machine is a high-energy optical system designed to remove surface layers through controlled interaction between laser radiation and matter. It is not a mechanical cleaner, not a chemical stripper, and not a replacement for every surface treatment method. It sits in the same category as CNC machining, laser welding, and laser marking: precision technologies whose success depends on process design, not brute force.

One of the most important things to know early is that laser cleaning does not clean by washing, scraping, or blasting. It works by selectively delivering energy to surface contaminants—rust, paint, oxides, oils, carbon, polymers—so those layers absorb energy faster than the base material. When done correctly, the unwanted layer detaches, decomposes, or vaporizes, while the substrate remains structurally intact.

This selective behavior is the reason laser cleaning can outperform traditional methods—but it is also why it fails when misapplied. If you approach laser cleaning expecting it to behave like sandblasting with light, you will choose the wrong machine, wrong settings, and wrong expectations.

Continuous-Wave vs Pulsed: A Foundational Decision

One of the first technical realities buyers must understand is that not all laser cleaning machines work the same way, even if they look similar externally.

Most industrial laser cleaning systems fall into two categories:

- Continuous-wave (CW) fiber laser cleaning machines

- Pulsed fiber laser cleaning machines

Both remove surface contaminants, but they deliver energy in fundamentally different ways.

Continuous-wave systems emit a steady laser beam while a scanning head moves it rapidly across the surface. They excel at:

- Heavy rust removal

- Thick oxide scale

- Large-area coating removal

- High-throughput industrial work

Pulsed systems emit extremely short, high-peak-power pulses with lower average heat input. They are preferred for:

- Mold and tool cleaning

- Weld preparation

- Thin materials

- Precision components

- Heat-sensitive substrates

A critical thing to know is that higher power does not automatically mean better cleaning. In many applications, a 200–300 W pulsed laser outperforms a 2000 W CW laser because it offers a wider safe process window. Buyers who chase wattage without understanding energy delivery often damage parts or struggle with inconsistent results.

Why Laser Cleaning Is Parameter-Driven, Not Operator-Driven

Another misconception is that laser cleaning quality depends primarily on operator skill. In reality, it depends far more on parameters.

Key parameters include:

- Average power

- Pulse energy and frequency (for pulsed systems)

- Scan speed

- Line spacing

- Spot size

- Number of passes

- Beam overlap

Together, these define fluence—the energy delivered per unit area. Every contaminant and substrate combination has:

- A removal threshold

- A damage threshold

Effective laser cleaning happens between those two values. Outside that window, cleaning is either ineffective or destructive.

This is why professional users develop cleaning recipes rather than relying on “feel.” Once validated, these recipes can be repeated with high consistency—one of laser cleaning’s biggest advantages over manual methods.

The Role of Optics and Scanning Systems

A laser cleaning machine is more than a laser source. The scanning head and optics are equally important.

Modern systems use galvanometer scanners to move the beam across the surface at very high speed. The scan pattern determines:

- Coverage uniformity

- Heat accumulation

- Striping or shadowing effects

- Edge behavior

Low-quality scanning systems limit effective cleaning width, create uneven energy distribution, and reduce productivity. This is a hidden differentiator between industrial-grade systems and entry-level machines that many buyers overlook.

Why Non-Contact Does Not Mean Zero Risk

Laser cleaning is non-contact, but that does not mean risk-free. High-energy light introduces hazards that are different from abrasives or chemicals, but no less real.

Laser radiation, reflections from shiny metals, airborne byproducts, electrical systems, and thermal effects all require engineering controls. Buyers who focus exclusively on cleaning performance often underestimate the importance of:

- Proper laser safety classification

- Certified eye protection

- Controlled work zones

- Effective fume extraction

Ignoring these factors does not just create safety risks—it undermines process stability and regulatory compliance, which ultimately affects cost and uptime.

Application Reality: Where Laser Cleaning Excels and Where It Does Not

Materials and Contaminants Laser Cleaning Handles Best

One of the most important things to know is that laser cleaning is selective by nature. It works exceptionally well on certain combinations of materials and contaminants.

Laser cleaning performs best on:

- Carbon steel with rust or scale

- Stainless steel oxides and heat tint

- Aluminum oxide layers

- Paints and industrial coatings

- Oils, grease, and machining fluids

- Carbon and soot residues

- Rubber and polymer mold deposits

These materials absorb laser energy efficiently relative to their substrates, creating a forgiving cleaning window.

Situations Where Laser Cleaning Is a Poor Fit

Equally important is knowing where laser cleaning struggles.

Laser cleaning is not ideal for:

- Bulk material removal

- Extremely thick, elastic coatings

- Deep internal cavities without line-of-sight

- Very low-value, high-volume commodity parts

- Applications where surface roughening is the primary objective

Trying to force laser cleaning into these roles usually results in poor economics or inconsistent quality.

Surface Preparation vs Surface Profiling

A subtle but critical distinction: laser cleaning is primarily a surface cleaning and activation technology, not a surface profiling technology.

Sandblasting creates roughness by impact. Laser cleaning creates cleanliness by removal. In coating applications, this distinction matters. In many modern coating systems, cleanliness is more important than aggressive roughness—but not always.

Knowing whether your downstream process requires cleanliness, roughness, or both is essential before committing to laser cleaning.

Laser cleaning machines are powerful, precise, and increasingly indispensable in modern industry—but they demand understanding. The most expensive mistakes are not buying the wrong brand; they are misunderstanding what laser cleaning is, how it works, and where it truly adds value.

This guide will continue in the next part, where we move from technology to economics—because knowing how laser cleaning works is only half the equation.

If you are already evaluating laser cleaning machines and want guidance grounded in real industrial use—not marketing claims, BOGONG Machinery works with manufacturers, contractors, and service providers to clarify applications, test materials, and select systems that make sense technically and economically. When you are ready to go deeper, a practical discussion beats assumptions every time.

Cost Reality, Ownership Economics, and Long-Term ROI of Laser Cleaning Machines

If Part 1 was about what laser cleaning really is, Part 2 is about the question that ultimately decides everything: does it make economic sense over time? This is where many laser cleaning projects succeed quietly—or fail expensively. The truth is that laser cleaning is neither cheap nor inherently expensive. It is capital-intensive, utilization-sensitive, and process-dependent. When those three realities are understood, the economics become predictable rather than speculative.

Laser cleaning machines are economically justified when they reduce total process cost, not when they are judged by purchase price or hourly operating cost alone. This distinction is critical, because laser cleaning shifts cost from consumables and rework into upfront investment and process control.

Capital Cost Is Fixed — Process Cost Is Variable

One of the most important things to understand about laser cleaning ownership is how cost structure changes compared with traditional cleaning methods.

A laser cleaning machine concentrates cost into:

- Laser source

- Optics and scanning head

- Cooling and electrical systems

- Safety and extraction integration

Once purchased, those costs are largely fixed. Whether the machine cleans one hour per week or eight hours per day, depreciation continues at the same rate. In contrast, sandblasting and chemical cleaning scale cost directly with usage through media, chemicals, waste disposal, and cleanup labor.

This means laser cleaning becomes cheaper per unit of work the more it is used. It rewards planning and integration. It punishes occasional, poorly scheduled use.

Understanding Total Cost of Ownership (TCO)

To judge cost effectiveness honestly, laser cleaning must be evaluated using a total cost of ownership model rather than a simple payback calculation.

A realistic TCO framework includes:

- Machine depreciation (typically 5–8 years)

- Electricity consumption

- Filter and fume extraction maintenance

- Optics inspection and replacement

- Labor

- Downtime avoided

- Rework avoided

- Waste disposal avoided

Below is a simplified comparison over time.

| Cost Element | Traditional Methods | Laser Cleaning |

|---|---|---|

| Upfront investment | Low–medium | Medium–high |

| Consumables | High, recurring | Low, predictable |

| Waste handling | High | Low |

| Rework | Medium | Low |

| Process variability | High | Low |

| Long-term cost trend | Rising | Declining |

This is why laser cleaning often looks expensive in year one and economical by year three.

Utilization: The Single Most Important Economic Variable

No factor influences laser cleaning economics more than utilization rate. A laser cleaning machine is a productive asset only when it is operating.

Consider this simplified illustration:

| Annual Operating Hours | Effective Cost per Hour* |

|---|---|

| 200 hours | Very high |

| 600 hours | Moderate |

| 1,200 hours | Low |

*Including depreciation, maintenance, energy, and filters.

This is why laser cleaning machines perform best when:

- Integrated into daily production

- Shared across departments

- Used for multiple applications

- Planned into maintenance schedules

Buying a laser “just in case” is rarely cost-effective. Buying one to replace a recurring pain point almost always is.

Why Laser Cleaning Reduces Hidden Costs

Traditional surface cleaning methods carry hidden costs that are rarely accounted for in simple comparisons.

Sandblasting, for example, often introduces:

- Surface over-roughening

- Embedded abrasive particles

- Masking labor

- Cleanup delays

- Inconsistent results between operators

Chemical stripping introduces:

- Chemical storage and handling

- Neutralization and rinsing

- Environmental compliance

- Drying time

- Residue risks

Laser cleaning reduces or eliminates many of these factors. The economic value does not appear on the cleaning invoice; it appears later in:

- Improved coating adhesion

- Reduced weld defects

- Longer component life

- Fewer rejected parts

- Shorter shutdown windows

In industries where failures are expensive, these savings dominate the ROI equation.

Energy and Consumables: Separating Myth from Reality

Laser cleaning is often described as “low energy.” That statement is context-dependent. While laser systems consume electricity, energy cost is typically minor compared with labor and consumables.

Electricity cost per hour is usually modest. What matters more is:

- Filter replacement intervals

- Extraction system efficiency

- Optics cleanliness

- Preventive maintenance discipline

These costs are predictable and controllable—unlike abrasive usage or chemical disposal, which fluctuate with job complexity and operator behavior.

Ownership vs Outsourcing Economics

Another important thing to know is when laser cleaning should be owned versus outsourced.

Owning a laser cleaning machine makes sense when:

- Cleaning is frequent

- Downtime is costly

- Quality requirements are strict

- Multiple applications exist

- Confidential or sensitive parts are involved

Outsourcing may be better when:

- Cleaning needs are rare

- Volume is unpredictable

- Capital is constrained

- Internal expertise is limited

Many successful companies start by outsourcing laser cleaning, then bring it in-house once volume and process stability justify ownership.

Lifecycle Thinking: Laser Cleaning as Infrastructure

Experienced users do not treat laser cleaning machines as short-term tools. They treat them as long-term infrastructure—similar to CNC machines, welding robots, or coating lines.

Over time, users often expand usage:

- From rust removal to weld prep

- From mold cleaning to surface activation

- From maintenance to inline production

As applications expand, utilization rises and unit cost falls. This is where laser cleaning shifts from “costly experiment” to “core capability.”

Takeaway

The most important thing to know about laser cleaning economics is this: the machine itself does not determine cost effectiveness—the way it is used does. Laser cleaning rewards disciplined integration, repeatable processes, and long-term thinking. It penalizes impulse purchases and underutilization.

If you are evaluating laser cleaning purely on purchase price or hourly cost, you are asking the wrong question. The right question is whether laser cleaning reshapes your total process cost in a durable way.

If you are unsure whether laser cleaning makes economic sense for your operation, BOGONG Machinery can help analyze your real applications, usage patterns, and cost structure before any equipment decision is made. A few hours of honest evaluation can prevent years of underutilized capital. When you are ready, we continue with Part 3—or we can switch directly to your specific use case and run the numbers together.

Business Models, Scaling Logic, and Why Most Laser Cleaning Operations Plateau

By the time a company reaches this stage with laser cleaning, the technology itself is no longer the problem. The laser works. The cleaning quality is proven. Safety systems are in place. Costs are understood. Yet this is exactly where most laser cleaning operations stop growing. Machines sit idle more often than expected. Margins shrink. The business feels “busy” but not scalable. This is not a technology failure—it is a business model and positioning failure.

Laser cleaning scales only when it is positioned as a specialized, value-driven process rather than a generic cleaning service. Operators who fail to make this shift almost always plateau at one underutilized machine.

The Three Dominant Laser Cleaning Business Models

Before discussing scaling, it is critical to understand which business model you are actually running. Most operators think they are in one model, but operate in another—often unknowingly.

The first model is general-purpose laser cleaning services. This is the most common entry point and the least scalable. The operator advertises “laser rust removal” or “laser cleaning services” broadly and accepts whatever jobs appear. While this generates early revenue, it leads to constant parameter changes, unpredictable scheduling, price pressure, and low repeatability. Growth stalls because every job feels like a new experiment.

The second model is application-specialist laser cleaning. Here, the operator focuses on one or two well-defined use cases—such as mold cleaning, weld preparation, or coating removal in a specific industry. Parameters are standardized, pricing becomes predictable, and repeat customers emerge. This model scales far better because each additional job looks similar to the last.

The third model is embedded laser cleaning, where the laser is not sold as a service at all. Instead, it is integrated into manufacturing, maintenance, or refurbishment workflows. The customer never buys “laser cleaning”; they buy better welds, longer mold life, or faster turnaround. This model delivers the highest long-term ROI but requires strategic thinking rather than transactional selling.

Most profitable operators consciously move from Model 1 to Model 2 or 3. Those who stay in Model 1 eventually hit a ceiling.

Why “Hourly Pricing” Kills Scalability

A critical thing to know—often learned painfully—is that hourly pricing is hostile to scale. When you sell laser cleaning by the hour, several negative dynamics appear:

- Customers compare you directly with sandblasting or grinding

- Efficiency improvements reduce billable hours

- Faster cleaning paradoxically reduces revenue

- Operators are incentivized to slow down

Professional operators eventually abandon pure hourly pricing in favor of:

- Per-part pricing

- Per-mold pricing

- Per-project pricing

- Contract or retainer models

When pricing is tied to outcomes rather than time, efficiency becomes an ally instead of an enemy. This shift is often the single biggest unlock for profitability.

Demand Concentration: The Hidden Growth Lever

Laser cleaning machines do not scale the way software scales. They scale through demand concentration—doing the same type of work repeatedly with minimal setup changes.

Successful operators deliberately concentrate demand by:

- Targeting one industry cluster

- Serving one geographic industrial zone

- Solving one recurring pain point exceptionally well

For example, an operator serving ten mold shops with weekly cleaning contracts is far more scalable than one serving fifty unrelated customers sporadically. Concentration reduces sales cost, increases utilization, and simplifies training.

Standardization: From Craft to Process

Another major barrier to scaling is over-reliance on individual expertise. If only one operator “knows the right settings,” growth stops when that person is unavailable.

Scalable laser cleaning operations document:

- Cleaning recipes by application

- Approved parameter windows

- Inspection criteria

- Safety checklists

- Setup and teardown procedures

This transforms laser cleaning from a craft into a repeatable industrial process. Once this transformation occurs, adding machines or operators becomes feasible.

When (and When Not) to Add a Second Machine

Many operators assume the next step is simply buying another laser. This is often premature.

A second machine makes sense only when:

- The first machine is utilized consistently

- Demand is predictable

- Pricing is stable

- Processes are standardized

- One machine is a bottleneck

Adding capacity without these conditions usually reduces margins. Fixed costs rise faster than revenue, and management complexity increases. The smarter path is often to increase utilization of the first machine before expanding.

Automation as a Scaling Tool, Not a Luxury

Automation is frequently misunderstood as something only large factories need. In laser cleaning, automation is often what makes scaling possible at all.

Robotic or gantry systems:

- Eliminate operator variability

- Improve safety

- Enable unattended operation

- Allow higher throughput

- Support contract-based pricing

Many successful operators use a hybrid approach:

- Handheld systems for irregular or onsite work

- Automated cells for repeat, high-volume tasks

This combination allows growth without sacrificing flexibility.

Why Marketing Laser Cleaning Is Hard—and How Professionals Do It

Laser cleaning is not intuitive to buyers. Many customers do not know it exists, or misunderstand what it can do. This makes marketing harder—but also creates opportunity.

Effective laser cleaning marketing:

- Focuses on customer pain, not laser specs

- Uses before/after evidence

- Demonstrates downstream benefits

- Speaks the customer’s industry language

Unsuccessful marketing talks about:

- Watts

- Pulse frequency

- Laser brand names

Successful marketing talks about:

- Downtime reduction

- Quality consistency

- Tool life extension

- Compliance simplification

The shift from “technology-first” to “problem-first” messaging is another key to scaling.

Why Most Laser Cleaning Businesses Plateau at Year One

Across markets, failure patterns repeat:

- Too broad positioning

- Inconsistent pricing

- Low utilization

- Overdependence on one operator

- No repeat contracts

Laser cleaning rewards focus. The operators who scale are not necessarily the most technical; they are the most disciplined in choosing what not to do.

Final Decision Logic, Selection Framework, and the Complete Laser Cleaning Picture

\ Laser Cleaning machine cost[/caption]

Laser Cleaning machine cost[/caption]

This final part closes the loop. By now, you understand what a laser cleaning machine is, how it works, where it fits technically, when it makes economic sense, how safety and workflow affect success, and why many businesses plateau despite owning capable equipment. What remains is the most important question of all: how do you make the right decisions—before and after buying—so laser cleaning becomes a durable advantage rather than an expensive experiment?

Successful laser cleaning adoption is not about buying the “best” machine. It is about aligning application reality, process discipline, utilization strategy, and business positioning into one coherent system. This section provides that system.

A Practical Decision Framework: Should You Use Laser Cleaning at All?

Before thinking about brands, power levels, or budgets, the first decision is binary: does laser cleaning belong in your process or business model at all?

Laser cleaning is a strong candidate when most of the following are true:

- The contaminant is a surface layer (rust, oxide, paint, oil, residue)

- The substrate must not be damaged or distorted

- Consistency matters more than brute force

- Waste, cleanup, or compliance is a pain point

- Downtime has real cost

- The same or similar jobs repeat over time

Laser cleaning is usually a poor fit when:

- Bulk material removal is required

- Surface roughening is the main objective

- Jobs are extremely low value and one-off

- Utilization will be very low

- Line-of-sight access is impossible

Answering this honestly prevents 80% of bad purchases.

Application-First Selection: The Question You Should Ask Suppliers

The most revealing question you can ask any laser cleaning supplier is not about power or brand. It is:

“Which of my specific applications has this exact configuration already been used on successfully?”

Professional suppliers will:

- Ask for material samples

- Discuss contaminants in detail

- Propose parameter windows

- Explain limitations openly

Weak suppliers will:

- Talk about wattage

- Show generic videos

- Avoid application-specific guarantees

Laser cleaning is application-driven by nature. If the application is not clear, the selection cannot be correct.

CW vs Pulsed: A Final, Clear Rule of Thumb

After all the nuance, the practical rule still holds:

- Choose continuous-wave (CW) laser cleaning when:

- Rust or scale is heavy

- Areas are large

- Throughput is critical

- Substrates are robust

- Choose pulsed laser cleaning when:

- Precision matters

- Parts are thin or heat-sensitive

- Mold, weld prep, or fine cleaning is involved

- Repeatability and control outweigh speed

Trying to force one type to do the other’s job is one of the most common—and costly—mistakes.

Power Selection: Why “Enough” Beats “More”

Power determines potential throughput, not guaranteed performance. Excessive power narrows the safe operating window and increases risk.

A better way to think about power:

- Select the lowest power that achieves your throughput target

- Preserve margin between cleaning threshold and damage threshold

- Favor stability over maximum speed

This approach produces better quality, easier training, and fewer rejected parts.

Ownership Strategy: Buy for Year Three, Not Day One

Another critical thing to know: laser cleaning ROI matures over time.

The first months are spent:

- Validating parameters

- Training operators

- Integrating workflows

- Educating customers (internal or external)

Real economic benefits usually appear when:

- Processes are standardized

- Utilization stabilizes

- Applications expand naturally

Buying the cheapest system often limits this evolution. Buying the most expensive system often delays break-even. The best choice supports growth without excess capacity.

A Simple Utilization Reality Check

Before purchase, answer these questions:

- How many hours per week will this machine realistically run?

- Which departments or customers will use it?

- What existing process will it replace?

- What happens if utilization is 30% lower than expected?

If the business case collapses under conservative assumptions, it is not ready yet. Strong laser cleaning projects survive pessimistic scenarios.

Common Myths That Lead to Bad Outcomes

Several persistent myths deserve explicit rejection:

- “Laser cleaning is maintenance-free.”

It is low-consumable, not maintenance-free. “Higher wattage means faster cleaning in all cases.”

Often false, especially for precision work.“One machine can handle everything.”

Rarely true without compromise.“If customers see the laser, they will pay more.”

Customers pay for outcomes, not light.

Understanding these myths protects both capital and credibility.

The Full Lifecycle View: Laser Cleaning as Capability, Not Equipment

The most successful users think of laser cleaning as a capability rather than a machine.

That capability includes:

- Defined applications

- Documented parameters

- Trained personnel

- Safe deployment

- Stable workflows

- Clear economic role

When any of these elements is missing, laser cleaning underperforms. When all are aligned, it becomes a long-term competitive advantage.

Final Conclusion: What You Really Need to Know About Laser Cleaning Machines

Laser cleaning machines are not hype, nor are they universal solutions. They are precision industrial tools that reward understanding and discipline. When applied correctly, they reduce waste, improve quality, shorten downtime, and open new business opportunities. When applied casually, they disappoint.

The most important things to know are not hidden in laser physics textbooks. They are practical truths:

- Application fit matters more than specs

- Utilization matters more than price

- Safety and workflow determine real-world use

- Focus beats generalization

- Long-term thinking beats impulse buying

If you remember these principles, laser cleaning will work for you—not against you.

A Real Conversation Before a Real Decision

If you have read this far, you are not casually browsing—you are evaluating a real decision. Whether you are considering your first laser cleaning machine, integrating laser cleaning into production, or building a service business, the fastest way to get clarity is to anchor the discussion in your actual application, not generic promises.

BOGONG Machinery works with manufacturers, contractors, and service operators to test real materials, define realistic process windows, and match laser cleaning systems to long-term technical and economic goals. If you want laser cleaning to become a reliable asset rather than an expensive lesson, start with a practical, application-driven discussion.

When you are ready, the right question is not “How powerful is the laser?”

It is “Will this system still make sense for me three years from now?”

Talk to Bogong Laser Cleaning Machines ExpertsGet a Quote or Customized Solution for Your Application

-

Whatsapp: +86-15665870861

-

Email: info@bogongcnc.com